The Book of Genesis is one of the oldest pieces of writing

that has survived to modern civilization. One of the reasons it’s stayed in our

collective memory so long is that it communicates profound truths about the

universe, life, and humanity. In describing the creation of the universe,

Genesis doesn’t assign an initial condition of void or nothingness. Before

light, before the great mystery that willed the universe into being, the abyss

is described as water. Such, the scribes who put ink to parchment all those

millennia ago imagined, it was at the beginning.

Perhaps this idea of water at the bedrock and basis of

existence is not a truth of the universe, but it is a fundamental truth of life

as we know it. Water is a not-quite-universal solvent, a carrier of ions,

magically, wonderfully liquid across a wide range of temperatures and

pressures. As creatures born of a watery ocean, we come with a biased

perception, but it’s difficult to imagine a better medium to bridge the gap

from chemistry to biology. Earth is lousy with water and equally lousy with

life. As we learned that the universe is so much vaster than our home planet,

it made sense to take an interest in water in the interest of finding how often

the universe stirs from the slumber of Genesis.

In the present day only two worlds are known to be blessed

with liquid waves washing their shores. Beyond the good Earth only Titan has

lakes, seas, waves, and rain. But Titan’s oceans are a truly alien landscape.

Water freezes to the consistency of steel at the surface, and methane flows

through the rivers and valleys of Saturn’s flagship moon. Perhaps life teems in

pockets of water deep under the surfaces of Europa, Enceladus, Pluto, and other

icy worlds far afield in the outer solar system. I hope that one beautiful day

this century a craft built by humans will report back the answer to these

questions. For now, though, those isolated havens are out of the grasp of our

technology and dreams.

The surface of Mars is a very difficult to place to reach by

any reasonable standard. It can, however, be reached. Today the planet seems

largely inhospitable to Earth’s simplest creatures with the greatest gluttony

for living in extreme conditions. There may be pockets deep underground or in

lakes beneath the polar glaciers that resemble Earth more closely, but the more

interesting comparison between Earth and Mars comes with a look backward in

time.

When I began high school the nature of Mars in the early

history of the solar system was a controversial topic. The spacecraft that had

orbited Mars found features that suggested the action of flowing water in the

distant past. It was plausible to imagine that long ago Mars had oceans, or at

least seas, mixing the same organic soup under the same sunlight as Earth.

Perhaps, the thought went, those seas begat life like the seas of Earth. Then again,

the three successful landers up to that time, the twin Vikings and Mars Pathfinder,

had little to say on the condition of ancient Mars. There were plausible

theories that didn’t require water and a thick atmosphere. Perhaps it was all a

case of looking at a mirage and seeing an oasis in the desert of deep space.

In the summer of 2003 two spacecraft launched from Earth to

settle the question. Their official name was an acronym in classic NASA

fashion. MER – the Mars Exploration Rovers. Shortly before launching they were

named Spirit and Opportunity.

From the start the mission had problems. Finding the ground

truth of the state of Mars four billion years ago required being able to move a

complex suite of spectrometers, cameras, and tools long distances. It was

unlikely that a single rock in the reach of a robotic arm wherever a spacecraft

happened to land would be able to give the full story. So the landers became

little more than packaging to bring the big rovers down to the surface.

The MER program didn’t have the budget to run a science

project to determine how best to get golf-cart-size rovers down to the surface

of Mars. 30 years earlier the Viking program launched rockets to Earth's upper atmosphere to test parachute deployment in

the most Mars-like conditions available on Earth. Spirit and Opportunity

would have to make do with knowledge already gained. The engineers had the

example of Pathfinder, and they

extrapolated on it to its insane conclusion. The rovers were too big. The

parachutes shredded when they inflated in tests over Idaho. The airbags burst over simulated Mars rocks. Meanwhile the planets moved in their orbits

and the launch window approached.

The parachute team iterated as fast as they could and found

a solution as the wife of the chief entry, descent, and landing engineer, Adam Steltzner, went into labor with their child. They added an additional

stabilizing rocket motor to the entry capsule to halt sideways movement as the

rovers approached the surface. Hopefully that would spare the airbags. They

made their schedules and launched when the heavens ordained they must, but only

just.

The night of July 7, 2003 was a typical summer night in

Florida. At Jetty Park, just south of Port Canaveral, the air was hot and muggy

and filled with the sound of insects and the watery surf of Earth crashing on

the beach. Several miles to the north, at the appointed time propellant valves

opened in the RS-27A engine powering the first stage of a Delta II launch

vehicle. The gas generator ignited, pouring exhaust gas black as coal and hot

as a blowtorch into the turbine. In a second the turbine spooled up, cranking torque through the gearbox and spinning the pumps to full power. A flame a

hundred times brighter than the gas generator began burning in the combustion chamber, the nozzle turning its luminous energy into thrust slamming the rocket

against its hold-down bolts, away from the Earth where it was made. Another second

went by, and six of the nine solid rocket motors ignited as the hold-down bolts

pyrotechnically split open. Opportunity,

the second rover, the backup MER, was off, never to touch the Earth again. At

Jetty Park bagpipes played "Amazing Grace"

and after half a minute the overwhelming roar of sound from the motors and engine

rattled in the ears and throats and bellies of all gathered there watching.

The ground-started motors burned out and fell away. The

remaining three solids ignited, turned their propellant into steam, ash, acid,

and kinetic energy, and fell away as well. When the RS-27A had consumed its

fill of kerosene and oxygen the computer closed the valves to shut down the

engine. The second stage ignited, and when the stack had climbed above the last

reaches of Earth’s atmosphere the protective fairing fell away from Opportunity. Nine motors and two engines

were insufficient for Opportunity to exit Earth’s gravity completely, so an additional spin-stabilized solid rocket motor

ignited for the final push away. Within half an hour of that moment on the

beach, the little rover would never again feel the water of Earth. It would one

day, perhaps, feel the trace of water of Mars.

As it happened, the Earth-Mars transfer window of 2003 was

very favorable. The two planets approached as close as they ever have in the

modern history of astronomy during that autumn, and six months later Spirit made her successful landing at

Gusev Crater. On January 25, 2004, it was Opportunity’s

turn at the gauntlet of atmospheric entry.

Mars is a much smaller planet than Earth. The transition

between interplanetary cruise and deceleration in the atmosphere is governed by

the mass of the planet. Smaller planet yields smaller orbital speeds and thus

lower atmospheric entry speed. Opportunity

hit the top of Mars’s atmosphere at a lower speed than a spacecraft

returning to Earth from low Earth orbit. From that relatively straightforward beginning,

descent to Mars only becomes harder.

At its lowest points the density and pressure of Mars’s

atmosphere is equivalent to the conditions high in Earth’s stratosphere. The

speed of sound in a gas is a function of molecular weight and temperature. Mars

is much colder on average than Earth, thus lower speed of sound. The upshot of

this atmospheric balance is that the Martian atmosphere is unable to slow an

entering spacecraft below the speed of sound unassisted. Like her twin Spirit and all other spacecraft that

have successfully landed on Mars, Opporutnity

had to deploy a soft parachute into air screaming by at twice the speed of

sound. The work of Steltzner and his colleagues was weighed in the balance and not found wanting. The parachute stayed

in one piece in the supersonic cacophony of deceleration.

Shortly before landing a solid-propellant gas generator

fired and the airbags surrounding Opportunity’s

landing platform inflated. The last set of solid rockets burned, bringing the

rover to a standstill for the first time in six months a few meters above the

dusty surface of Mars. A pyrotechnic initiator fired, cutting the cord between Opportunity and the last machine that would

ever carry it. The rover bounced for a time in the leisurely gravity of Mars,

then rolled to a halt in a little crater the team at JPL named Eagle.

Opportunity proceeded

cautiously but impatiently. The rover was only certified to last for 90 Martian

days. It was essential not to do anything that could compromise the workings of

her delicate instruments, but it was also essential that she not fall asleep

under the cold pink Martian sky before the cameras and spectrometers probed

what they were there to find. So in those first few months Opportunity stepped off the landing platform and became a creature

of Mars.

The dust of Eagle Crater was littered with ball bearing-shaped

concretions. It was evident that the bedrock was full of them, and they were

rolling out as the outcrop eroded away. As the instruments attacked the

rock one by one at site after site the picture they revealed was unmistakable.

For a long time, long ago, there was water here. Mars was warm. Mars had seas,

perhaps oceans. Winds blew on sandy shores then, just as they do now on Earth.

This was not circumstantial evidence, but ground truth.

The rover was healthy, so she pressed on. The plains of her

new home, Meridiani Planum, were studded with meteorites. As the rover’s

longevity became more apparent she moved from one crater to another. Endurance,

Victoria, Endeavour Craters all hosted the rover for a time. The months became

years. The staff on Earth went back to measuring their days in Earth time. The

planets moved in their orbits. In Pasadena the seasons progressed through their

cycle and in Florida the launches continued on their regular cadence. Phoenix joined the pair for an arctic

summer. Spirit became mired in a sand

dune and fell silent a year later. Curiosity

arrived as Opportunity reached

Endeavour Crater. Opportunity slowed when the dust accumulated on her solar

panels, then leaped into action again when dust devils brushed them clean.

At Endeavour she found a vein of gypsum. Even more than the

discoveries at Eagle Crater, this indicated a long, benign period in the

ancient history of Mars. There might have been little to distinguish Earth’s

and Mars’s conditions at that time on the surface. We now know that bacteria

and archea can survive the acceleration and jerk of asteroid impacts and

exposure to space for years, perhaps centuries, at a time. The geological

record of Earth and the Moon suggests that the time when life existed on Earth

overlaps the time when Earth’s surface was routinely sterilized by cataclysmic

impacts. All life on Earth began as space travelers, it appears. So, perhaps it’s

not so far-fetched to suggest that Mars was a second home, or perhaps even a

first home, for the life that now dwells upon the Earth. Perhaps, the idea is thrilling to entertain, Opportunity's journey to Mars was really a homecoming for life that began on Martian shores.

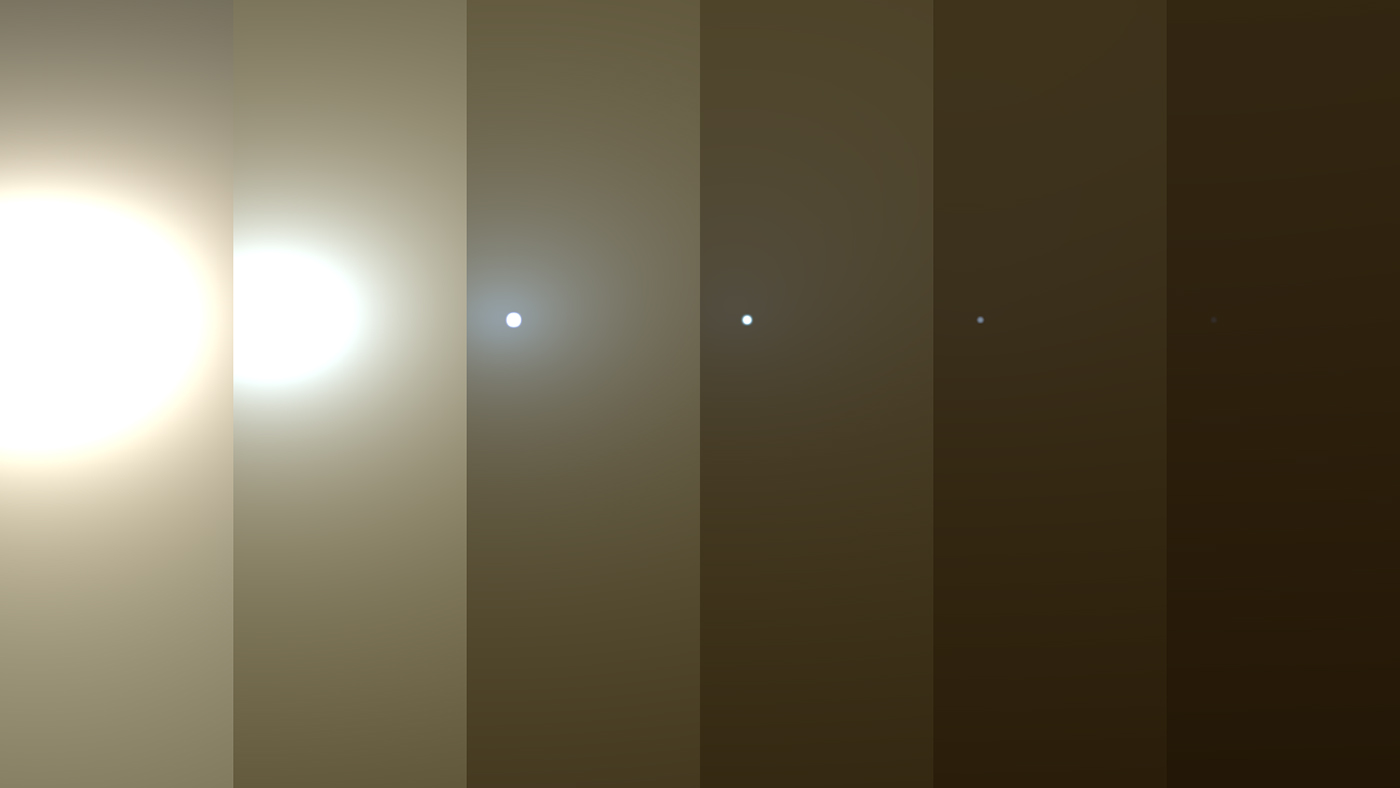

Last year, after Opportunity

had been on Mars for 14 Earth years and traveled 28 miles, a particularly vicious

dust storm began during the Martian southern spring. The atmosphere turned an

ugly smoggy brown and it went dark at Meridiani. While the nuclear-powered Curiosity carried on at Gale Crater and InSight wound its way through deep space

toward Mars, the Sun failed to reach Opportunity’s

solar panels and her batteries ran down. She went silent on June 10, 2018.

For a long time there seemed to be hope that she would wake

up and begin her mission of exploration and discovery once again. The controllers

at JPL waited patiently. The dust began to settle from the atmosphere. They

uploaded commands to the rover from the great radio antennas at Goldstone,

Canberra, and Madrid. No response. It seems when the batteries drained the

temperature of the rover fell below the point where the electronic brains and

heart of the rover began to fail. The little plutonium heaters were

insufficient to shut out the relentless cold of a world that did not birth them.

Opportunity will not speak or move

under her own power again.

Opportunity has

been on Mars for half of my life. Both MER rovers, but especially Opportunity, have utterly transformed

our collective human understanding of Mars and of the place of water and life

in the solar system. Meanwhile my own life has changed beyond recognition. I

went through high school, through college, and began working on the design of

rockets to reach orbit, my passion from childhood. So many people and events

touched my life in that time. I met the woman I married, who I share my life

and children with. I met many friends, and sadly I’ve wandered away from many

of them as the planets move and the years go by and the endless waves splash the

dirty organic beaches of Earth.

In college I became friends with a woman who now works as a

mission operations engineer at JPL. We shared a passion for the wonder and

beauty of the universe beyond Earth. That shared passion brought us together

for a few years of projects and get-togethers in Students for the Exploration

and Development of Space at Texas A&M, then it sent us different directions

as we pursued our interests separately. Today she signed the paperwork for the

final planned attempt to contact Opportunity.

There was a melancholy in this moment, knowing that the mission of so many

years and dreams was coming to an end. But also, for me at least, there was a

thrill to be this close to such an astonishing piece of history. My children will never know a Mars that wasn't warm and wet long ago, thanks in large part to these rovers. I hope that

Keri Bean and the others at JPL who were the last people to say farewell shared

in this feeling as well. The rest of humanity, marveling at the mysteries

revealed, thanks you.

One day there will be living, laughing, breathing humans on

Mars. For now we send our robotic emissaries, but one day we'll make the journey

ourselves. One day some of those people will likely venture to the Spirit and Opportunity landing sites. Perhaps they will keep their distance,

letting the rovers rest in the final locations their wheels and motors brought

them. Perhaps they will gather them gently, clean the dust from their solar

panels, and place them in a museum. Whatever they do, I’m sure they’ll look in

wonder at what humans from the beginning of the 21st Century were

able to do, and the wonders that these little machines showed on the big world

they explored.